In 2015 Billfold writer Ester Bloom unwittingly got on the wrong side of The Daily Show‘s Jessica Williams. What unfolded next holds important lessons for anyone grappling with impostor syndrome.

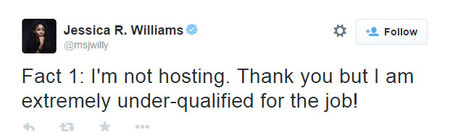

It all began when the actress and comedian tweeted her response to the groundswell of fan support to replace departing anchor Jon Stewart.

For someone as accomplished as Williams to describe herself as “extremely under-qualified” just didn’t ring true to many admirers, Bloom among them. So she wrote a post in which she described Williams as the “latest victim of impostor syndrome.”

First, to the uninitiated, impostor syndrome describes an experience shared by millions of intelligent and well-adjusted women and men who, despite overwhelming evidence of their abilities, secretly believe they’re not as bright or talented as everyone “thinks” they are. There’s no shortage of successful people in the news and entertainment world who, as Mike Myers put it, still expect the “no-talent police” to come and arrest them. Tina Fey, Don Cheadle, Kate Winslet, Renee Zellweger, Jody Foster, Rachel Maddow, producer Chuck Lorre, and countless others have talked openly about their fraudulent feelings.

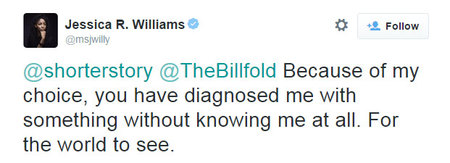

But Williams made no such public declaration. So understandably took issue with being labeled, tweeting:

An indignant Williams went on to issue a series of tweets including this one.

For those who really do feel like impostors, readiness can be elusive. There’s always one more book to read, one more revision to write, one more degree to earn before you dare pronounce yourself “ready.” Unfortunately, this relentless pursuit to reach the elusive “end” of knowledge or experience can cause people to take months or sometimes even years longer than necessary to achieve a goal.

On the flip side, to Williams point, there are times when we genuinely aren’t ready. Just as Clint Eastwood’s character in Magnum Force famously said, “A man’s got to know his limitations,” so too does a woman. In fact, a healthy respect for our limitations is itself a form of competence. It’s also what keeps more of us from winding up on other end of the confidence continuum alongside those who are afflicted with a lesser-known but arguably far more dangerous condition known as Irrational Self-Confidence Syndrome (ISC) – a wonderfully apt term coined by former Rocky Mountain News reporter Erica Heath to describe the unjustifiably confident.

If you’ve watched contestants audition for shows like America’s Got Talent, then you’ve seen people who seem unable to recognize the true limitation of their talents. On television it’s comical. But it’s not so funny if you’ve ever had to work with or under a poor performer who can talk a good game.

To be clear: this is not the same as the healthy confidence that comes from accepting that you can’t possibly know everything but jumping in anyway. Rather it’s about 1) recognizing that the world would be a better place if more people respected where their expertise and experience ends and someone else’s begins and 2) embraced the idea that you are both capable of figuring things out as you go along and that, with obvious exceptions like performing surgery or flying a 747, it really is okay to do so. That kind of confidence is not only a good thing, it’s essential in overcoming impostor feelings.

In other tweets Williams framed her no-go decision to anchor, not in terms of readiness or qualifications, but rather as a matter of personal choice, writing:

“Because you have personally decided, that I DON’T know myself- as a WOMAN you are saying that I need to lean in. Are you unaware, how insulting that can be for a fully functioning person to hear that her choices are invalid? If I wanted my personal choice for myself deemed invalid, I’d go to a mysoginist (sic). This, quite honestly, hurt my feelings. Also don’t call me a ‘victim’? How can you call me a ‘victim’ for making a choice for myself. I’m sorry but how? “

From the outside, Williams clearly has the talent to anchor. However, there really is a distinction between ability and desire – a distinction that can easily be lost on people who feel like impostors. After all, if you believe your achievements have been largely a fluke, then naturally the idea of becoming even more successful is going to be stressful. There’s more responsibility. More people counting on us. The stakes are higher. There’s further to fall. And of course with each new success, the increased chance you’ll be found out.

At least that’s what my friend “Sharon” discovered when she was being actively courted for a significantly higher-level position. The new job would put her in charge of more people and a larger operation. It also came with a huge salary bump. I could tell from Sharon’s voice that she was excited – and scared.

I’ve studied impostor syndrome longer than Jessica Williams has been alive. So I knew Sharon wanted me to talk her down off the impostor ledge. To remind her how normal it is to feel nervous when faced with a new challenge. That she was more than capable of handling any challenge that came her way. That she’d be crazy not to take what was clearly an incredible opportunity.

But that’s not what happened. Instead, I simply said, “Maybe you just don’t really want it.” In seconds, Sharon went from shock to relief. Make no mistake about it, my friend was afraid to take the job, although as she came to see, not totally because she didn’t think she could do it.

What happened to Sharon happens to a lot of “impostors.” We become so used to those niggling voices of self-doubt that we totally forget to heed other voices. Voices that may have far more to do with who we are and what we want than they do with how much we know and what we can do. Once we’re consciously aware of these things we can, like Williams, sort out for ourselves, “Am I hesitant because I don’t think I can do it, or do I just not want ‘it.’”

What makes the “lean in” discussion so complicated for people who feel like impostors is that anxiety or ambivalence can so easily be confused with lack of confidence. In reality, as Williams reminds us, any number of non-confidence-related reasons could be in play.

Maybe you have a more layered definition that goes beyond the traditionally more male emphasis on money, power, and status to include things like balance or satisfaction. If you’re already feeling caught between a clock and a hard place, then you could be hypersensitive to the additional demands that come with increasing levels of success. If you’re being asked to break new ground as the first woman, a person of color, an individual with a disability, religious minority, or as the youngest, you may not be up for the unavoidable pressure that comes with having to represent your entire social group.

Success is complicated. Which is why I hardly ever talk about impostors being “afraid” of success.

That’s not to say success can’t be intimidating or even downright terrifying, because it can – and all the more so if you think you’re a fraud. However, I believe everyone has a powerful inner desire to succeed. And given where she sits at just 25 years old, Jessica Williams would seem to be no exception.

This article first appeared in the Huffington Post.

You are welcome to reprint this post with the bio below.