Watch the video below for BONUS CONTENT on The 5 Types of Impostor Syndrome…

Want more valuable coaching insights and tools like this? Click the button below for details about our acclaimed Impostor Syndrome-Informed Coach™ program.

Watch the video below for BONUS CONTENT on The 5 Types of Impostor Syndrome…

Want more valuable coaching insights and tools like this? Click the button below for details about our acclaimed Impostor Syndrome-Informed Coach™ program.

I’ve spent close to four decades helping people who feel like impostors, fakes, and frauds.

In that time, I’ve come to an important conclusion:

If you want to truly put yourself on the fast track to feeling as bright and capable as you really are, then nothing — and I do mean nothing — will get you there quicker than adjusting your beliefs about what it takes to be competent.

Why? Because the impostor syndrome goes beyond a mere lack of confidence.

Everyone experiences bouts of self-doubt from time to time — especially when attempting something new.

But because “impostors” have insanely high self-expectations, the self-doubt is chronic.

It’s also possible to doubt your abilities without believing that you ultimately succeeded because of some sleight of hand or that you are fooling others.

A person could have normal jitters before, say getting up to give their first speech, do well, and then draw from this experience to feel more confident about the next time.

But “impostors” don’t think this way.

Because no matter how well you did or how loud the applause, you find a way to explain them away.

It was a great audience. They just like me. Fooled ’em again.

So wins don’t produce any real bump in confidence.

This is where it helps to understand the 5 types of impostor syndrome.

Twenty years of well-documented research, by leading expert in motivation and personality psychology Carol Dweck, author of Mindset, confirmed what I’d discovered from my own research in the early 1980s.

Namely, your notion of what it means to be competent has a powerful impact on how competent you feel. It’s also at the core of impostor feelings.

It’s why one of the first exercises I created for my impostor syndrome workshops was called, “What’s in Your Rule Book?” Some three decades later and I still use this exercise today.

Everyone has unconscious rules in their head about what it means to be competent. These rules tend to begin with “should,” “always,” or “never.”

Whether it’s ivy league students or engineers at Boeing or IT managers at IBM — the exercise elicits the same basic rules.

If I were really intelligent, capable, competent…

My personal favorite was the Stanford Ph.D. student who said, “I feel like I should already know what I came here to learn.”

Which of course, is absurd.

I’ve done this exercise with people from all walks of life and at all phases of their careers.

Nurses, engineers, professors, biologists, Ph.D. candidates, social workers, physicians, jewelers, accountants, financial advisers, senior executives, chemists, programmers, entrepreneurs, attorneys — even romance book writers.

And each time it confirms my early findings.

Namely, because people who feel like impostors hold themselves to an unrealistic and unsustainable standard of competence, falling short of this standard evokes shame.

However, it was only after doing the rule book exercise with tens of thousands of people that I made a second discovery.

Impostors don’t all experience failure-related shame the same way. And the reason is that they don’t all define competence the same way.

What emerged from the rules exercise are five different Competence Types (commonly referred to as the 5 types of impostor syndrome) — each with its own unique focus:

The fact that everyone else sees a highly capable individual where you see an inadequate fraud, is a pretty good indicator that you operate from a competence playbook that bears little resemblance to reality.

It doesn’t matter how intelligent or talented or skilled you are right now, I have news for you.

You are never going to consistently reach that insanely high bar you’ve set for yourself – ever.

That’s why if you truly want to beat the impostor syndrome you must adjust your self-limiting thinking as to what it takes to be “competent.” This redefining process is bar none, your fastest path to confidence.

I know you want to stop feeling like an impostor. But that’s not how it works.

In fact, feelings are the last to change.

Do you want to stop feeling like an impostor? Then you have to stop thinking like an impostor.

And rewriting your inner rule book by understanding the 5 types of impostor syndrome is hands-down the best place to start.

An extensive description of the 5 competence types, including solutions for each, can be found in Chapter 6: The Competence Rulebook for Mere Mortals in The Secret Thoughts of Successful Women: Why Capable People Suffer from Impostor Syndrome and How to Thrive in Spite of It*, Valerie Young, Crown Business, 2011

Click here to download a free chapter

You are welcome to reprint this post with the bio below.

I facilitated my first impostor syndrome workshop in 1985.

Titled Impostors Fakes and Frauds: Issues of Confidence and Competence for Women it was based largely on the findings from my doctoral research.

Since then, some things have changed.

For starters, for many years workshop attendees were almost exclusively female students, engineers, professors, attorneys, physicians, and other professionals. No surprise when you consider impostor syndrome is one of the few psychological issues first thought to be specific to women that was later found to impact men too.

But in the past decade especially, I’ve seen a marked shift. Not only are more people who identify as male attending my talks, but in some cases, men make up half the room.

(A far cry from 2006 when Inc. magazine had to look to me to help them find a successful male entrepreneur to admit to impostor feelings.)

However, when I began my doctoral research in the early 80s, impostor syndrome was still thought to be a female issue.

I didn’t study impostor syndrome per se.

Instead, I wanted to understand the internal barriers as well as the socio-cultural expectations and realities that might lead women to feel like impostors.

My research consisted of in-depth interviews with 15 professional women – a majority of whom were women of color.

Subjects worked in human resource or training roles in a range of environments including corporate, education including state and Ivy League colleges and a women’s technical training school, a career guidance center, and a program designed to help older women entering or re-entering the paid work world.

Since my focus was women naturally, my conclusions and resulting recommendations for designing educational and other solutions were aimed at helping this audience as well.

Fast forward 36 years and thousands of speaking engagements later and although the solutions I put forth in 1985 are essentially the same as those I offer today, there is one difference.

Now I know the crux of my original findings applies to everyone with impostor syndrome:

Take for instance this passage from the Summary and Conclusions section of my dissertation. If you replace “women” with “people who feel like impostors,” the core problem – and solution – remain the same.

Issues related to performance (meaning here how women experience themselves relative to success, failure, and competence) were considered critical in comprehending the ways in which women may limit themselves occupationally.

For example, women are frequently stymied by a definition of competence which presumes that they must perform with perfection and that furthermore, this must be done without the aid of others.

The expectation too is that in order to competent, they must demonstrate expertise in all endeavors and in multiple roles. As a consequence, women often attach a certain mystique to those they deem to be competent and hence, dismiss themselves as inadequate by comparison.

The yardsticks people who feel like impostors use to measure their own failures and successes are similarly warped. Failures become internalized, achievements are externalized.

Worse, women typically do not feel they have the right to fail nor to succeed. Fearing the real and imagined cost of failure as well as the perceived price and responsibility of success, they are left in a kind of achievement limbo.

By over-identifying with one, under-identifying with the other, feeling entitled to neither and fearing both, they are denied an accurate, internalized picture of their own abilities which, ultimately renders them unable to learn from their failures, embrace their successes, and exorcise the erroneous and crippling view of themselves as intellectual impostors.*

I’d been aware of Stanford psychologist Carol Dweck’s research for many years.

But it was not until 2007 when she published her brilliantly accessible book Mindset that I fully realized just how closely Dweck’s extensive qualitative findings tracked with what I’d discovered years earlier through my own qualitative research.

In brief, Dweck found that people who hold themselves to unrealistic standards, who become fixated on being “smart” and experience shame at failure — something she refers to as a “fixed mindset” – score higher for impostor feelings.

This notion that how you define and experience competence, success, and failure has everything to do with how confident and competent you feel is something I’d preached for decades.

Other things have remained consistent. Like the well-documented and persistent confidence gap between men and women.

And the connection between internal feelings of fraudulence and systematic factors.

The same external expectations and realities I cited in 1985 continue to cause women, people of color, first-generation students or professionals, people with disabilities, and indeed, anyone on the receiving end of stereotypes about competence and intelligence to be especially susceptible to fraud feelings today.

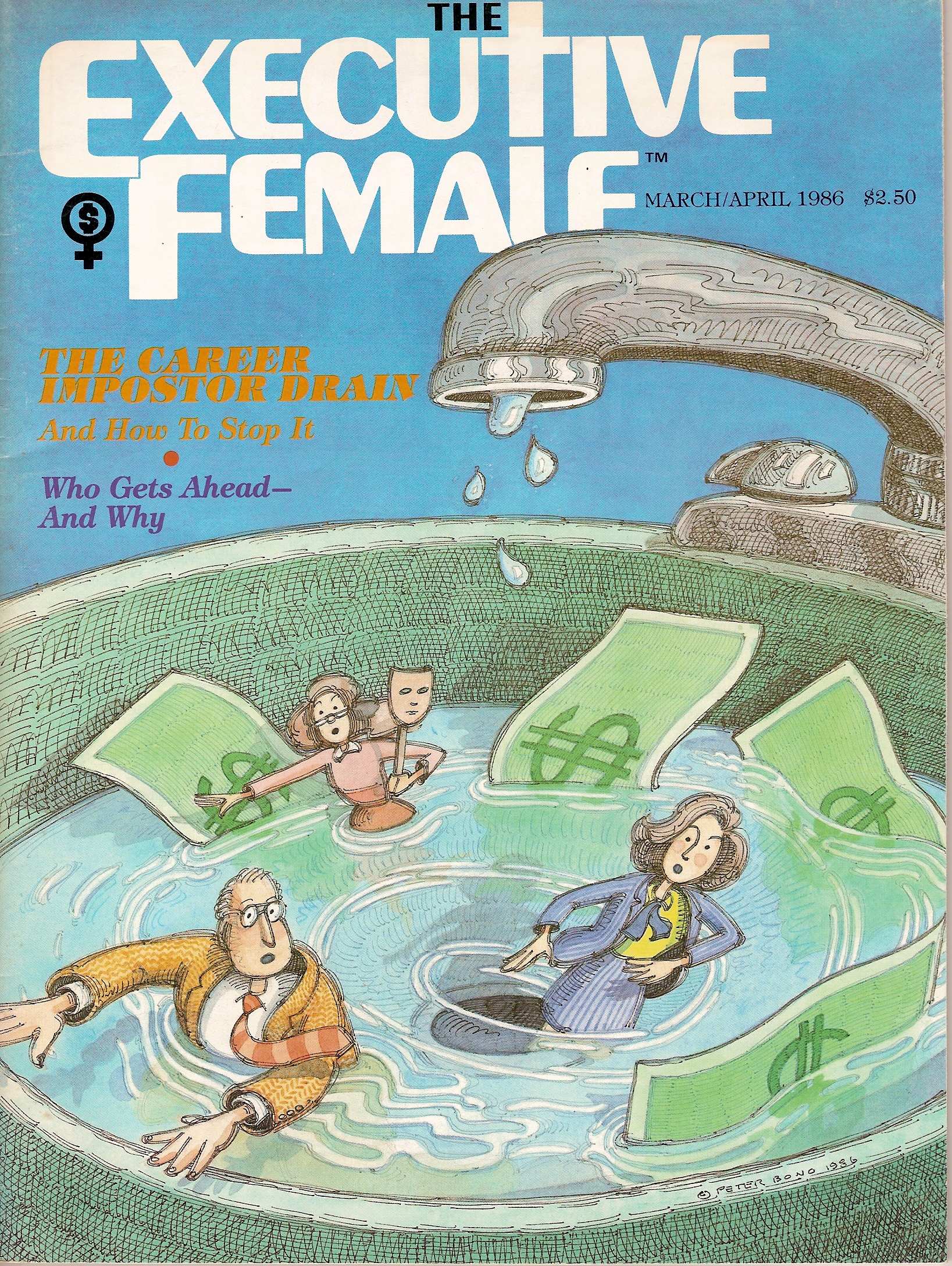

A related constant is a need for organizational solutions to impostor syndrome much along the lines of those I laid out in a 1986 edition of Executive Female magazine.

We do need systemic changes.

In fact, no one should be speaking or coaching on impostor syndrome if they’re not talking about the larger intersection between it and diversity and inclusion or about the ways organizational culture can fuel self-doubt.

In the meantime, if you’re among the majority of people who experience impostor syndrome, you don’t have to wait for systemic or organizational change to start applying the same core “cure” I recommended in 1985 and today, namely:

The only way to stop feeling like an impostor is to stop thinking like an impostor.

Not only is adjusting how you think about competence, failure, and success bar none the fastest path to interrupting impostor syndrome, it won’t happen unless you do.

* Doctoral dissertation: A model of internal barriers to women’s occupational achievement, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 1985

You are welcome to reprint this post with the bio below.

I just received notice from Random House that a publisher in Bulgaria wants to publish my book!

That makes translations in Italian, Korean, Czech, Portuguese, Spanish, Russian (in Ukraine), and later this year, Ukrainian and Turkish.

I’m not telling you this to impress you.

I’m telling you this to underscore that the global demand for solutions to impostor syndrome has never been stronger.

And with that, the need for informed coaches, mentors, and advisors who can effectively address this multifaceted and often highly nuanced issue has never been greater.

How do you become “that coach”?

For starters, you don’t need coaching solutions that are overly simplistic.

You also don’t need solutions that are overly theoretical.

And since you never want to cross the line into therapy, you don’t want solutions that over-psychologize impostor syndrome.

Finally, you certainly don’t want cookie-cutter coaching solutions like “make a list of your accomplishments” or “embrace failure.”

It begins with knowing how to help your clients (or yourself) to “flip the script.”

Not by positioning impostor feelings as some kind of “superpower”

Not by encouraging them to name, tame, or befriend their “inner critic.”

Or, by assuming that your client’s ability to overcome impostor syndrome relies entirely on you uncovering and healing a core childhood wound…

A wound you could spend years searching for that may not even exist.

I’m not talking about the egotistical braggers whose confidence exceeds their abilities.

You see, the opposite of impostor syndrome isn’t arrogance or incompetence.

The true opposite of impostor syndrome is the person I call a “Humble Realist™.”

Humble realists are not “smarter” or more skilled.

They’re not eternally confident.

The difference is that when faced with the same situation that triggers impostor feelings in your client (or you)…

…like a job interview, public speaking, a promotion…

Humble Realists™ are thinking different thoughts.

To be clear: This isn’t about a pep talk…

“You’ve got this!” “You can do it!” “You deserve to be here!”

All of which is true.

But when it comes to impostor syndrome, it’s not going to move the needle in any lasting way.

Besides, if all it took were some encouragement, impostor syndrome would have disappeared long ago.

To be truly effective, we must address a normal psychological process known as cognitive distortions.

The American Psychological Association defines cognitive distortions as faulty or inaccurate thinking, perception, or belief.

Examples include over-generalizing, all-or-nothing thinking, personalization (it’s my fault; it must be me), “should-ing,” catastrophizing, and disqualifying positives by attributing them to external factors.

All things people with impostor feelings do.

A central finding from my early academic research was the key connection between impostor syndrome and inaccurate thinking, perceptions, or beliefs specifically about competence.

“Competence distortions” is a term I coined to refer to the idealistic and unsustainable ways we judge our intellect and performance.

Failure to consistently attain our unrealistic notions of competence confirms we are “impostors.”

Competence distortions are the core of impostor syndrome

Put another way…

There’s a lot more to it, of course…

But essentially, competence distortions tie into my discovery of what’s become known online as the five types of impostor syndrome.

The 5 Types of Impostor Syndrome.

(The concept must resonate because, last I checked, the term netted nearly 5 million Google results!)

A big part of unlearning impostor syndrome involves knowing how to help yourself or others to reframe competence.

To be clear, reframing is not the same as coaching clients to “talk to yourself like you would your best friend” or “challenge your inner critic.”

It’s about knowing how to help them adopt a more realistic understanding of what it means to be “competent.”

And it’s a whole lot easier to fix the way we think than it is to try to “fix” ourselves.

Besides, approaches that stress positive self-talk fail to consider the extent to which people with impostor syndrome conflate competence and confidence.

How in the minds of many people, the fact that they struggle with confidence in the first place, “proves” they must be an impostor.

This is unsurprising considering the prevalence of promises to “banish your inner critic forever” and “achieve unshakable confidence in yourself.”

But what happens when your client does blow the presentation or the big sale or the moment? (Which being human, they occasionally will!)

Then what?

That’s why you need a proven coaching framework designed specifically for clients with impostor syndrome.

You see, deep down, your clients with impostor syndrome know they are no impostor.

If pressed, they’ll likely acknowledge that they really do know they have the capacity to achieve most goals they will set for themselves in life.

Not quickly or easily. Not perfectly or masterfully or without help. Not without mistakes, setbacks, or, yes, failure.

But on some level, your clients really do know they can do just about anything they set their mind to.

It is just that all that limiting “impostor thinking” gets in their way.

The Bottom Line:

If you see the value in advanced training and the opportunity to earn ICF CCEs, click here to learn about the new ON DEMAND Impostor Syndrome-Informed Coach™ program now available to anyone, regardless of timezone or schedule.

Join coaches in 22 countries using the leading evidence-based method that turns self-doubt into lasting confidence — for your clients and yourself.

By submitting this form you give consent to use this information to send additional emails and communication as described in our Privacy Policy